Published: February 2018

Prepared by: The Research Directorate, Immigration & Refugee Board of Canada

This Report was prepared by the Research Directorate of the Immigration and Refugee Board (IRB) of Canada based on approved notes from meetings with oral sources, publicly available information, analysis and comment. All sources are cited. This Report is not, and does not purport to be, either exhaustive with regard to conditions in the country surveyed or conclusive as to the merit of any particular claim to refugee protection. For further information on current developments, please contact the Research Directorate.

Table of Contents

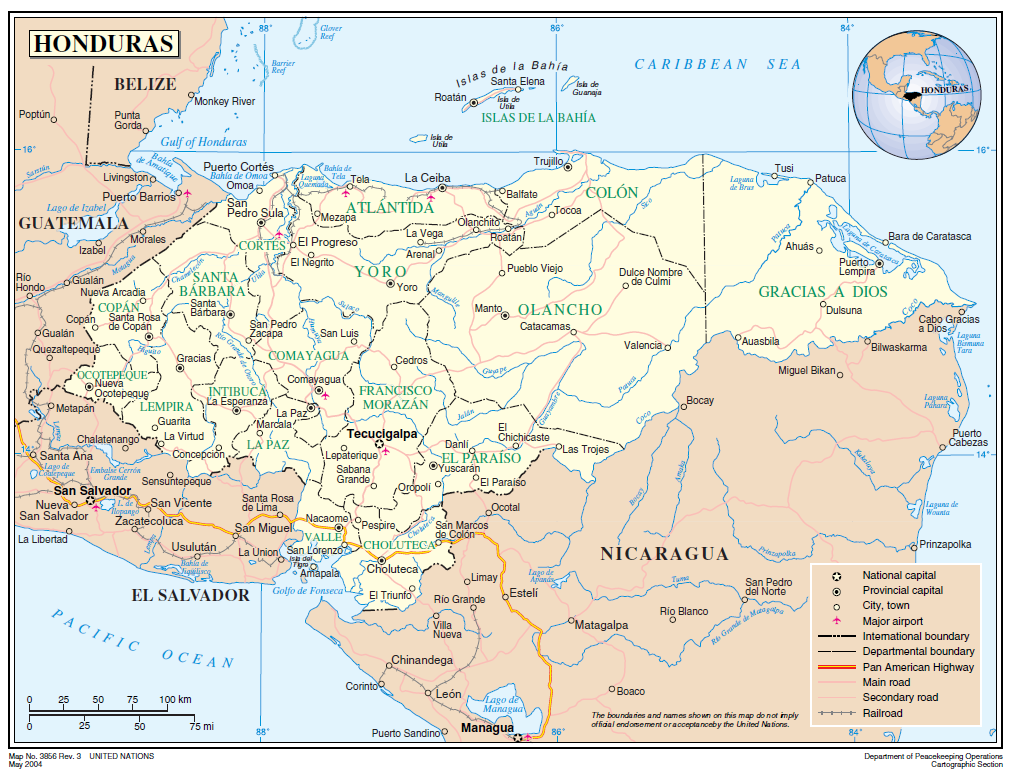

Map

Source: United Nations (UN). May 2004. Department of Peacekeeping Operations, Cartographic Section. "Honduras." [Accessed 1 Aug. 2017]

Glossary

-

ACAP

Asylum Cooperation Action Plan -

ACV

Asociación Calidad de Vida (Quality of Life Association) -

APUVIMEH

Asociación Para Una Vida Mejor de Personas Infectadas y Afectadas por el VIH/SIDA en Honduras (Association for a Better Life for Persons Infected and Affected by HIV/AIDS in Honduras) -

ATIC

Agencia Técnica de Investigación Criminal (Technical Agency of Criminal Investigation) -

CAMR

Centro de Atención a los Migrantes Retornados (Centre for the Assistance of Returned Migrants) -

CAPRODEM

Centro de Atención y Protección de los Derechos de las Mujeres (Centre for Care and Protection of Women's Rights) -

CdA

Centros de Alcance (Outreach Centres) -

CDH

Centro de Desarrollo Humano (Centre for Human Development) -

CDM

Centro de Derechos de Mujeres (Centre for Women’s Rights) -

CEM-H

Centro de Estudios de la Mujer (Centre for Women’s Studies) -

CENISS

Centro Nacional de Información del Sector Social (National Centre for Information on the Social Sector) -

COBRA

Comando de Operaciones Especiales (Special Operations Command) -

COI

Country of Origin Information -

COMAR

Comisión Mexicana de Ayuda a Refugiados (Mexican Commission for Refugee Assistance) -

CONADEH

Comisionado Nacional de los Derechos Humanos (National Commissioner for Human Rights) -

CPTRT

Centro de Prevención, Tratamiento y Rehabilitación de Victimas de la Tortura (Centre for the Prevention, Treatment and Rehabilitation for Victims of Torture) -

DINAF

Dirección de Niñez, Adolescencia y Familia (Directorate for Children, Adolescents and Family) -

DNII

Dirección Nacional de Investigación e Inteligencia (National Directorate of Investigation and Intelligence) -

DESA

Desarrollos Energéticos S.A. (Energy Developments S.A.) -

DPI

Dirección Policial de Investigaciones (Police Directorate of Investigations) -

ECLAC

Economic Commission for Latin America and the Caribbean -

ERIC-SJ

Equipo de Reflexión, Investigación y Comunicación – Compañia de Jesús (Critical Thinking, Research and Communication Team – Society of Jesus) -

FUNDEVI

Fundación para el Desarrollo de la Vivienda Social, Urbana y Rural (Foundation for the Development of Urban and Rural Social Living) -

GSC

Grupo Sociedad Civil (Civil Society Association) -

IACHR

Inter-American Court of Human Rights -

ICRC

International Committee of the Red Cross -

IDMC

International Displacement Monitoring Centre -

IDPs

Internally Displaced Persons -

ILGA

International Lesbian, Gay, Bisexual, Trans and Intersex Association -

NAM

Instituto Nacional de la Mujer (National Institute for Women) -

INM

Instituto Nacional de Migración de Honduras (Honduran National Institute of Migration) -

IOM

International Organization for Migration -

IRB

Immigration and Refugee Board of Canada -

IRCC

Immigration, Refugees, and Citizenship Canada -

M-18

Barrio 18 -

MACCIH

Misión de Apoyo contra la Corrupción y la Impunidad en Honduras (Mission to Support the Fight against Corruption and Impunity in Honduras) -

MAU

Movimiento Amplio Universitario (Broad University Movement) -

MS-13

Mara Salvatrucha -

NGO

Non-governmental organization -

NHL

Lempiras -

NRC

Norwegian Refugee Council -

OAS

Organization of American States -

PLAN

Programa Nacional de Prevención, Rehabilitación y Reinserción Social (National Program for Prevention, Rehabilitation and Social Reintegration) -

PMH

Pastoral de Movilidad Humana (Human Mobility Pastoral) -

PLCSC

Plan Local de Convivencia y Seguridad Ciudadana (National Plan for Citizens' Coexistence and Security) -

PPT

Programa de Protección a Testigos (Witness Protection Program) -

RAD

Refugee Appeal Division -

RPD

Refugee Protection Division -

SDHJGD

Secretaría de Derechos Humanos, Justicia, Gobernación y Descentralización (Ministry of Human Rights, Justice, Governance and Decentralization) -

SRE

Secretaría de Relaciones Exteriores (Ministry of Foreign Affairs) -

SOGI

Sexual orientation and gender identity -

UMAR

Unidades Municipales de Atención a Migrantes Retornados (Municipal Units for Assistance to Returned Migrants) -

UN

United Nations -

UNAH

Universidad Nacional Autónoma de Honduras (National Autonomous University of Honduras) -

UNHCR

United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees -

USAID

United States Agency for International Development -

USCIS

United States Citizenship and Immigration Services -

WHO

World Health Organization

Introduction

In 2013, Canada and the United States of America (US) began working together to identify opportunities to establish new modes of cooperation in the areas of asylum and immigration; this collaboration is known as the Asylum Cooperation Action Plan (ACAP). The ACAP, through the department of Immigration, Refugees and Citizenship Canada (IRCC), approached the Immigration and Refugee Board (IRB) of Canada to seek the IRB's support for capacity-building activities to be undertaken in the Americas with the objective of improving asylum systems in the region. In May 2015, the Deputy Chairperson of the IRB's Refugee Protection Division (RPD) participated in a meeting between Canada, Mexico and the United States, where it was agreed that the IRB would undertake a number of activities to support the development of quality refugee status determination in Mexico. One such activity was IRB participation in a series of joint country of origin information (COI) gathering missions to El Salvador, Honduras, and Guatemala; key source countries in Mexico's asylum case load.

Under the auspices of the United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees (UNHCR) in Mexico and El Salvador, a joint information gathering mission was conducted in April 2016 to El Salvador by researchers from the IRB and participants from the Mexican government's Commission for Refugee Aid (Comisión Mexicana de Ayuda a Refugiados, COMAR), the Mexican Ministry of Foreign Affairs (Secretaría de Relaciones Exteriores, SRE), and the United States Citizenship and Immigration Services (USCIS). The mission resulted in two research reports produced by the IRB:

Gangs in El Salvador and the Situation of Witnesses of Crime and Corruption and

The Situation of Women Victims of Violence and of Sexual Minorities in El Salvador.

A second joint mission was conducted in Honduras in April 2017, including a researcher from the IRB, participants from COMAR and the SRE, and the UNHCR. Representatives of the Mexican Embassy in Honduras also participated. The joint mission was carried out from 3 to 7 April 2017. The purpose of the mission to Honduras was to gather COI as it relates to: state efforts to combat crime; criminal gangs, including their areas of operation, activities, and recruitment practices; the situation of violence against women and girls; the situation of sexual minorities, including LGBTI (lesbian, gay, bisexual, trans, and/or intersex) persons; and the ability and efficacy of the state, police and judiciary to provide recourse to victims of crime, as well as to investigate and prosecute crimes.

The IRB would like to thank the Embassy of Canada in Honduras and the UNHCR for providing logistical support and assistance during the mission.

Methodology

The mission to Honduras consisted of a series of meetings with community representatives, experts, and officials from relevant governmental, non-governmental, academic, and research-focused organizations. For details on the organizations and individuals consulted during this mission, please refer to the section entitled "Notes on Interlocutors" at the end of this Report. The interlocutors chosen to be interviewed were identified by the delegation based on their occupation and their expertise. However, given the time constraints in which the delegation had to undertake the mission, the list of sources should not be considered exhaustive in terms of the scope and complexity of human rights issues in Honduras. Meetings with interlocutors were coordinated by the office of the UNHCR in Honduras and took place in the interlocutors' offices, or at the UNHCR offices in Tegucigalpa and San Pedro Sula. All interviews were conducted in Spanish.

Interview questions posed to interlocutors were formulated in line with the Terms of Reference for the mission (see

Appendix 1). Interviews were conducted using a semi-structured approach so as to adapt to the expertise of the particular interlocutor(s) being interviewed. The Terms of Reference were developed in consultation with joint mission participants and the IRB’s decision-makers from the RPD and the Refugee Appeals Division (RAD). Interlocutors' responses to these questions varied depending on their willingness and ability to address them, and the length of time granted for the interview.

In accordance with the Research Directorate's methodology, which relies on publicly available information, interlocutors were advised that the information they provided would be used to produce a report on country conditions in Honduras. In this regard, interview notes were sent to interlocutors for their approval. Furthermore, interlocutors were asked to consent to being cited by a professional title or by their institution for the information they provided. They were informed that this report is publicly accessible and may be used by decision-makers adjudicating refugee claims in Canada.

This Report is divided into three chapters and is based on the information gathered by the IRB during the mission to Honduras, as well as publicly available documentary sources. The first chapter examines the situation of crime, gangs, internal relocation, and state protection mechanisms available for victims of crime, including state programs to assist returnees. The second chapter provides information about violence against women and girls, as well as the recourse available to them. The third chapter provides information about the situation of sexual minorities and recourse available to them.

This Report may be read in conjunction with several IRB publications, including the following Responses to Information Requests:

Overview

Honduras has an estimated population of 8,576,532 people and a land area of approximately 112,492 square kilometers.Footnote 1 Honduras has 18 departments and 298 municipalities.Footnote 2 The government consists of three branches, namely a legislative, an executive, and a judicial branch.Footnote 3 Legislation is established through codified law, special laws and written administrative regulations.

Footnote 4 Laws are “only valid once the enactment procedure is completed and [laws] come into force once they are published in the Official Gazette.”Footnote 5 In December 2017, Juan Orlando Hernández of the Partido Nacional de Honduras [National Party of Honduras] was re-elected as the President of Honduras.Footnote 6

Honduras is considered one of the poorest countries in the world

Footnote 7 and the second poorest country in Central America.

Footnote 8 It is estimated that more than 60 percent of its population lives in poverty.Footnote 9 Its economy depends mostly on trade with the US, and remittances sent from the Honduran diaspora in the US, with its main exports being bananas and coffee.

Footnote 10 Other exports include shrimp and tilapia.Footnote 11

Honduras is also considered one of the most violent countries that is not at war.Footnote 12 A significant amount of violence occurs in some of the poorest communities in the country.Footnote 13 The US Department of State's

Country Reports on Human Rights Practices for 2016 indicates that, in Honduras, "[o]rganized criminal elements, including local and transnational gangs and narcotics traffickers, were significant perpetrators of violent crimes and committed acts of murder, extortion, kidnapping, torture, human trafficking, and intimidation of journalists, women, and human rights defenders."Footnote 14 Criminal groups operating in Honduras include transnational drug trafficking organizations, street gangs, and local smuggling organizations.Footnote 15 Honduras is a transit country for drugs being transported from South America to North America.Footnote 16 As such, Colombian and Mexican drug trafficking organizations have a presence in the country,Footnote 17 including the Sinaloa Cartel,

Footnote 18 Gulf Cartel and Los Zetas.Footnote 19 The mission learned that street gangs, especially the Barrio 18 (M-18) and Mara Salvatrucha (MS-13), are engaged in killings, extortion, street-level drug trafficking, forced displacement, disappearances, threats and intimidation. Local smuggling organizations are engaged in the legal and illegal movement of goods throughout the country and have international connections.Footnote 20

According to sources, the root causes of violence in Honduras are unemployment,Footnote 21 lack of access to education,Footnote 22 family disintegration,Footnote 23 economic inequality,Footnote 24 easy access to firearms,Footnote 25 corruption,Footnote 26 and a lack of effective long term policies to address these problems.Footnote 27 It was indicated to the mission that violence is "normalized" in the sense that it is seen as a typical occurrence by Honduran citizens.Footnote 28 That is, to be a witness to violence, but remain silent, is a common method of survival.Footnote 29

In 2011, the Honduran government instituted a security tax to fund the state's national security projects.Footnote 30 For background information on the security tax, see Response to Information Request HND104993 of 10 December 2014. The website of the Honduran government indicates that between 2012 and 28 February 2017, the government collected approximately 14.1 billion lempiras (NHL) [approximately C$768.7 million] through the security tax initiative.Footnote 31 Between 2012 and 28 February 2017, 38 percent of the tax was distributed to the Ministry of Public Safety (Secretaría de Seguridad), 32 percent to the Ministry of Defense (Secretaría de Defensa), 17 percent to the National Directorate of Investigation and Intelligence (Dirección Nacional de Investigación e Inteligencia, DNII), 5 percent to the Public Ministry (Ministerio Público), and 2 percent to the Supreme Court (Corte Suprema), while funding for prevention programs amounted to 5 percent.Footnote 32 Claudia Flores indicated that the population has not benefited from the ways that the income from the security tax has been spent.Footnote 33

The mission learned that social leaders, student activists and journalists are subject to intimidation by state agents and criminal organizations. According to the Ministry of Human Rights, Justice, Governance and Decentralization (Secretaría de Derechos Humanos, Justicia, Gobernación y Descentralización, SDHJGD), human rights advocates are routinely criminalized and threatened by criminal organizations and state security forces.Footnote 34 US

Country Reports 2016 similarly states that "[h]uman rights defenders, including indigenous and environmental rights activists, political activists, labour activists, and representatives of civil society working to combat corruption, reported threats and acts of violence."Footnote 35 Student activists have been pressured by police officers to stop their advocacy work inside universities and they are also coerced by gangs to join them.Footnote 36 According to Radio Progreso, independent journalists are frequently barred from press conferences by state officials.Footnote 37 Journalists also practice self-censorship on issues such as drug trafficking.Footnote 38 Police officers and prosecutors suggest to journalists that they refrain from publishing information related to violence or corruption in order to avoid retaliation from criminal groups.Footnote 39

According to the Honduran government, the homicide rate in 2016 was 57.7 homicides per 100,000 inhabitants.

Footnote 40 However, interlocutors indicated that the homicide statistics presented by the government tend to be lower than the actual number, and as a result, do not reflect the real situation.Footnote 41 According to the National Observatory on Violence (Observatorio Nacional de la Violencia) of the Autonomous National University of Honduras (Universidad Nacional Autónoma de Honduras, UNAH), there were 5,150 homicides in 2016, representing a rate of 59.1 per 100,000 inhabitants.

Footnote 42 The departments with the highest homicide rates in 2016 were Atlántida (414 homicides - a rate of 90.6 homicides per 100,000 inhabitants), Cortés (1,469 homicides - a rate of 88.8 homicides per 100,000 inhabitants), Francisco Morazán (1,129 homicides - a rate of 71.6 homicides per 100,000 inhabitants), and Yoro (420 homicides - a rate of 70.5 homicides per 100,000 inhabitants).

Footnote 43 The municipalities with the highest homicide rates in 2016 were La Ceiba (120.8 homicides per 100,000 inhabitants), San Pedro Sula (107.3 homicides per 100,000 inhabitants), and the Central District, which includes Comayagüela and Tegucigalpa (82.3 homicides per 100,000 inhabitants).Footnote 44 The Pastoral de Movilidad Humana (PMH) has documented cases of homicides that are not reported to authorities as criminal organizations kill people and then order family members to bury the victim without telling authorities.Footnote 45 In such cases, families are not able to obtain death certificates,Footnote 46 nor are such deaths captured in official homicide statistics.Footnote 47

The mission learned that firearms proliferation is a serious problem in Honduras. Estimates on the number of legal and illegal weapons in Honduras vary.Footnote 48 In 2014, a commission established by the Honduran Congress estimated that there are approximately 400,000 registered weapons and 700,000 weapons that circulate illegally in the country.Footnote 49 In a 2016 interview with the Small Arms Survey, officials of the National Arms Registry (Registro Nacional de Armas) in Tegucigalpa reported that between 450,000 and 500,000 firearms were registered to private citizens.

Footnote 50 According to the law, a citizen is allowed to legally possess up to five firearms.Footnote 51

Chapter I. Crime in Honduras and the Situation of Witnesses of Crime and Corruption

1. Territorial Presence

The mission learned that gangs have a presence in the majority of communities throughout Honduras. The mission also learned that gangs exert territorial control over their areas of influence.Footnote 52 Territorial control is important for gangs.Footnote 53 Gangs consider residences in their territory as their property and as such, control the lives of the inhabitants.Footnote 54 One way of exerting territorial control is through curfews, which are "normalized" inside communities, and a violation of a curfew can be fatal.Footnote 55 While the gang phenomenon used to be mainly urban,Footnote 56 it has been expanding into rural areas.Footnote 57

1.1 Invisible Borders

The mission learned that gang territories are defined by invisible lines or invisible borders and that gangs are well-informed about the people crossing into their territories. Crossing these borders, on purpose or inadvertently, can lead to the person being killed.Footnote 58 Even in the presence of police patrols alongside these invisible borders, people who cross without permission are at risk of being killed.Footnote 59

Several interlocutors indicated that students are at risk of being killed for crossing the invisible borders that separate schools from their homes.Footnote 60 The Norwegian Refugee Council (NRC) indicated that during a weekend in 2016, approximately 40 children from a local school had to be transferred to another school as the invisible border that was present in that area had shifted.Footnote 61 The new local gang warned that they would kill any "non-resident" student who attended school the following Monday.Footnote 62 According to NRC, situations like these not only put a strain on other schools' resources, but transferred children are accused by other students for exposing their school to gang violence.Footnote 63

In general, non-residents seeking to enter neighbourhoods controlled by gangs need to request permission from the gangs.Footnote 64 Permission can be obtained through community organizations,Footnote 65 the local priest or a religious leader.Footnote 66 One of the protocols established by gangs for non-residents entering their territory is to lower the windows of vehicles while in the neighbourhood, in order to identify the individuals inside of the vehicle.Footnote 67

Social workers and non-governmental organizations (NGOs) who go to schools to deliver programs must receive authorization from gangs to do so,Footnote 68 as well as receive gang approval of the content of the educational program.Footnote 69 Asociación Calidad de Vida (ACV) provided the example that students who are part of gangs routinely ask visiting social workers and advocates, in front of teachers and school administration officials, to identify themselves and to provide a debrief on the content to be presented in the classes.Footnote 70 The Directorate of Social Services (Gerencia de Apoyo a la Prestación de Servicios Sociales) of the Municipality of San Pedro Sula indicated that in three of San Pedro Sula's neighbourhoods, it is difficult to send an educator to cover a shift at a school in an area where he or she does not live, because he or she will be at risk.Footnote 71 As a result, the Municipality of San Pedro Sula struggles to recruit educators who live in the same area as the school.Footnote 72 The mission also learned that there have been cases of school closures due to gang violence.Footnote 73

1.2 Recruitment

Criminal groups are persistent in their recruitment efforts.Footnote 74 Interlocutors indicated that youth in Honduras usually have two options: join the gangs or leave the neighbourhood to other parts of the country or outside the country.Footnote 75 One of the reasons why youth join gangs is to be part of a group that can protect them.Footnote 76 They are led to believe that these entities are organizations to which they can belong, that they can trust, and where they can find protection.

Footnote 77 Others join as a strategy to avoid being killed by gangs.Footnote 78

In addition, many families have been forced to give away their children to the gangs.Footnote 79 Interlocutors indicated that forced recruitment of children causes families to leave their communities.Footnote 80 In many other cases, parents confine their children to their house and do not let them attend school so they do not get recruited and/or killed.Footnote 81 According to NRC, there are cases where parents and family members lie about their child having a serious medical condition in order to dissuade gangs from forcibly recruiting that child.Footnote 82 PMH indicated that family members caring for children eventually send them on the migratory route (ruta migratoria)Footnote 83 to prevent gangs from recruiting them.Footnote 84 One of the ways girls try to avoid recruitment is through early pregnancies, hoping that this will deter interest from gang members.Footnote 85

The mission learned that gangs recruit children as young as 10 years old.Footnote 86 PMH has documented recruits as young as five and seven years old who are being trained to commit crimes.Footnote 87 In some cases, gangs drug children in order to train them to use weapons and to kill people.Footnote 88 They start out with "easy" targets to kill, but by the time they are 16 or 17 years of age, they are fully trained to assassinate for the gang.Footnote 89 Gangs also use minors, as young as six years old,Footnote 90 as look-outs (banderas) to let them know when non-residents are entering the neighbourhood.

Footnote 91

Gangs also use women as

banderas and as bait to kill targeted persons.Footnote 92 In addition, gangs use children to transport drugs between areasFootnote 93 or to sell drugsFootnote 94 in schools, for example.Footnote 95

The mission learned that the number of gang members in Honduras varies from source to source. A research report by Public Safety Canada indicates that the numbers range between 6,000 and 36,000, depending on the source consulted.Footnote 96 Dr. Ayestas indicated to the mission that the number of gang members is actually hard to determine, although it is estimated that the number of gang members is 30,000.Footnote 97 According to InSight Crime, it is difficult to establish who is a gang member and who is a collaborator, as the line that divides both roles is not clear.Footnote 98 InSight Crime explained that "collaborators" are those who provide assistance to gangs, but are not part of the gangs themselves.Footnote 99 Collaborators include street drug dealers, lawyers, taxi drivers and mechanics who provide services to the gangs, as well as intelligence.Footnote 100

The National Program for Prevention, Rehabilitation and Social Reintegration (Programa Nacional de Prevención, Rehabilitación y Reinserción Social, PLAN) indicated that gangs usually respect the lives of members who quit the gang to join religious organizations.Footnote 101 However, according to the Directorate of Children, Women and Family (Dirección de Niñez, Mujer y Familia) of the Municipality of San Pedro Sula, people who leave the gang are persecuted throughout the country.

Footnote 102 Other interlocutors similarly indicated that gangs have the ability to locate targets throughout the country.Footnote 103 The mission learned that people fleeing extortion, recruitment, and people who they suspect have filed a complaint with authorities, are common targets of gangs. The mission learned that gangs have communication networks with other cliques (clicas),

Footnote 104 not only throughout the country, but also with cliques of the same gang in other countries in the Northern Triangle. Casa Alianza gave the example of Honduran asylum seekers kept in Mexican detention centres who felt unprotected, since their persecutors were able to find them due to the presence of gang members in those same detention centres.Footnote 105 The mission also learned that gangs have communication networks inside state institutions.

1.3 Activities

The mission learned that gangs are involved in killings, extortion, street-level drug trafficking, forced displacement, disappearances, threats and intimidation. Gangs also invest in legal enterprises such as taxis, gas stations and hotels.Footnote 106 Contract killing has become a lifestyle and another form of income for many gang members,Footnote 107 and they can reportedly be carried out for as low as 200 HNL [approximately C$10.80].Footnote 108 The mission learned that gangs displace entire families in order to occupy their houses.Footnote 109 These houses, which are called "crazy houses" (casas locas), are used by gangs to kill people and to dismember their bodies.Footnote 110 The mission learned that dismembered bodies are discarded in sacks in public areas.Footnote 111

1.3.1 Extortion

Extortion is one of the main drivers for both internal and external displacement.

Footnote 112 Many families are forced to leave their home because they are not able to pay the extortion fee, which is known as the "war tax" (impuesto de guerra).Footnote 113 Casa Alianza has heard cases of persons being extorted for 200,000 HNL [approximately C$10,800], to be paid within 24 hours.Footnote 114

Students and teachers are regularly threatened and extorted.Footnote 115 Public transportation drivers, commonly known as

transportistas,

Footnote 116 are specifically targeted for extortion.Footnote 117 Extortion is the root cause of most attacks and killings of public transportation drivers in the country.Footnote 118 Public transportation drivers are often required to pay up to three extortion amounts to different gangs.Footnote 119 Amounts extorted typically range between 200 HNL [approximately C$10.80] and 300 HNL [approximately C$16.20].Footnote 120

When the National Commissioner for Human Rights (Comisionado Nacional de los Derechos Humanos, CONADEH) handles cases concerning victims of extortion and threats, it requests that security measures be taken by the State Secretary of Security (Secretaría de Estado en el Despacho de Seguridad).Footnote 121 In recent years, security measures have consisted of random patrols sent to the victim's residence.Footnote 122 According to CONADEH, however, these measures are not comprehensive and are delayed.Footnote 123

2. Legal Apparatus and Institutional Efficacy

2.1 Justice System

The mission learned that mistrust in the justice system is widespread among the population.Footnote 124 Honduras has high levels of impunityFootnote 125 and investigation into crimes is inefficient.Footnote 126 US

Country Reports 2016 indicates that "[c]orruption and impunity remained serious problems within the security forces. Some members of police committed crimes, including crimes linked to local and international criminal organizations."Footnote 127 Radio Progreso indicated that 95 percent of assassinations go unpunished.Footnote 128 Other sources indicate that in Honduras, 80 percent of crimes go unsolved.Footnote 129 The Organization of American States' (OAS) Mission to Support the Fight Against Corruption and Impunity in Honduras (MACCIH), which started its operations in Honduras in April 2016, works to combat corruption and impunity by, for example, assisting and strengthening Honduran state institutions, to prevent, investigate and punish acts of corruption.Footnote 130 One of MACCIH's areas of work is [translation] "enhancing the criminal justice system and reducing high levels of impunity," including by improving access to justice, reducing judicial delays, improving criminal investigation mechanisms, effectively administrating the penal process and optimizing the quality of sentences.Footnote 131

2.2 National Police

The mission observed a lack of police presence on the streets in San Pedro Sula and Tegucigalpa. The BBC reports that Honduras has 13,500 police officers and 15,000 soldiers.Footnote 132 Radio Progreso estimated that there are approximately 14,000 police officers and 13,000 soldiers.Footnote 133 The National Police in San Pedro Sula is divided into four metropolitan units and each metropolitan unit has 200 police officers, including those employed in administrative functions.Footnote 134

Dr. Ayestas indicated that private security companies have a greater capacity to provide security than the National Police and the armed forces.Footnote 135 Radio Progreso indicated that private security firms have more than 75,000 guards.Footnote 136 Other sources indicate that there are approximately 750 security firmsFootnote 137 employing around 120,000 people.Footnote 138

According to sources, there are police officers who have been accused of committing extortion.Footnote 139 Interlocutors indicated that the National Police has being going through an internal purge to dismiss corrupt officers from the force.Footnote 140 Following revelations concerning the involvement of police officials in the killing of antidrug officials, the Special Commission for the Purging and Transformation Process of the National Police (Comisión Especial para el Proceso de Depuración y Transformación de la Policía Nacional) was set up in April 2016 to lead the police purge.Footnote 141 According to Dr. Ayestas, almost 50 percent of police officers have been dismissed during this process.Footnote 142 News sources report that 4,934 police authorities were evaluated, of which 2,581 have been dismissed, including high ranking officials (28 percent), support staff (4 percent), and low ranking officials (68 percent).Footnote 143 The Centro de Prevención, Tratamiento y Rehabilitación de Victimas de la Tortura (CPTRT) indicated that the purge has not been effective as it has focused on lower ranking officials, rather than those in higher ranks.Footnote 144

2.3 Protection Programs

2.3.1 Witness Protection Program

Honduras has a witness protection program, Programa de Protección a Testigos (PPT), which is run by the Public Ministry.Footnote 145 Sources indicate that witness protection provided by the Public Ministry is inefficient,Footnote 146 due to the lack of resources, for example.Footnote 147 CONADEH indicated that the number of protection requests is "out of proportion" compared to the limited financial and human resources available, which hinders the ability of the state to provide effective protection.Footnote 148 CONADEH indicated that it provides, in coordination with the Public Ministry, economic assistance to protected witnesses, including assistance to relocate witnesses to other parts of the country, depending on the particular situation of the person.

Footnote 149 In some cases, CONADEH coordinates with NGOs to relocate protected witnesses abroad.Footnote 150 PMH has documented cases of persons in the witness protection program who were turned over to their aggressors by the officials that were in charge of protecting them.Footnote 151 CPTRT indicated that witnesses face risks, including death, as protection offered to them is limited to six months on average, while a trial can last up to two and a half years.Footnote 152 For additional information about PPT, see Response to Information Request HND105348 of December 2015.

2.3.2 Protection Program for Human Rights Defenders, Journalists, Media Workers, and Justice Operators

Honduras has a protection program available for human rights defenders, journalists, media workers, and justice operators.

Footnote 153 The protection program, which was created under the 2015

Law for the Protection of Human Rights Defenders, Journalists, Media Workers, and Justice Operators (Ley de Protección para las y los Defensores de Derechos Humanos, Periodistas, Comunicadores Sociales y Operadores de Justicia), is administered through the National System for the Protection of Human Rights Defenders (Sistema Nacional de Protección para Personas Defensoras de Derechos Humanos).Footnote 154 For 2017, the National System had a budget of 25 million HNL [approximately C$1,350,259].Footnote 155 It has issued protection measures to 85 persons, including 56 human rights defenders, 16 journalists, 4 media workers, and 9 justice operators.

Footnote 156 Title III of the Law, which includes information about protection measures and the process to request such protection, is attached to this Report (Attachment 1).

SDHJGD indicated that evaluations of applications for protection originating from outside Tegucigalpa are conducted over the phone, as the SDHJGD does not have the necessary infrastructure in other parts of the country to handle these protection requests.Footnote 157 In some cases, and depending on the nature of the case, the SDHJGD requests the assistance of CONADEH to conduct interviews in its offices outside of Tegucigalpa.Footnote 158 A notification letter is provided to those who are admitted for protection under this program.Footnote 159

SDHJGD indicated that, although the protection program is only available for specific groups, some employees at the SDHJGD have assisted other victims of violence by providing them with information and advice on how to deal with their personal circumstances.

Footnote 160

Radio Progreso indicated that the protection mechanism established by the 2015

Law for the Protection of Human Rights Defenders, Journalists, Media Workers, and Justice Operators does not work in practice.Footnote 161 The Movimiento Amplio Universitario (MAU) indicated that the government's witness protection measures for human rights advocates is inefficient and that student activists, who have been threatened, prefer seeking support from NGOs to relocate to other parts of the country or abroad.

Footnote 162 MAU explained that student activists have been criminalized and subjected to arbitrary detention and irregular judicial proceedings, adding that between 2015 and 2017, around 120 criminal processes were launched against student activists for crimes, including sedition, misappropriation, and damage to public property.

Footnote 163 The mission learned that journalists and human rights advocates do not trust the police for protection.

Footnote 164 Radio Progreso explained that members of the National Police and armed forces have been accused of assaulting journalists who cover protests.

Footnote 165

2.3.3 Precautionary Measures

According to Article 25 of the Rules of Procedure of the Inter-American Commission on Human Rights (IACHR) of the OAS, the IACHR may, "on its own initiative or at the request of a party, request that a State adopt precautionary measures."Footnote 166 According to the IACHR, Precautionary Measures "may be of a collective nature to prevent irreparable harm to persons due to their association with an organization, a group, or a community with identified or identifiable members."Footnote 167 In order to carry out IACHR’s requests for Precautionary Measures, OAS States have issued protection measures for beneficiaries, which can include “bodyguards, security at office buildings, direct lines of communication with the authorities, protection of ancestral territory, and others.”Footnote 168 The mission learned, however, that activists in Honduras with Precautionary Measures issued by IACHR are regularly threatened, while some have been killed. Berta Cáceres, a highly recognized land rights advocate and indigenous leader, was killed on 3 March 2016 in La Esperanza, in the Department of Intibucá.Footnote 169 Cáceres had Precautionary Measures ordered by the IACHR since 2009; however, prior to her killing, she had indicated that she was constantly being harassed and intimidated.Footnote 170 Cáceres had reported that she received 33 death threats for her campaign against the construction of a hydroelectric dam by a company with "extensive military and government links."

Footnote 171

2.4 Violence Prevention Programs

The mission learned of the existence of several social programs to prevent violence and to assist victims, including youth. For example, according to PLAN, there are schools that offer education centres with alternative programs for youth, including violence prevention programs and extracurricular activities.Footnote 172 The Municipality of San Pedro Sula offers vocational training courses to disadvantaged youth, such as carpentry, computer training, appliance repair, and esthetics, so they can obtain employment and become economically self-sufficient.Footnote 173 These programs, which range between six months and two years, are offered at three technical institutes located in Chamelecón, Villas Mackay and Las Palmas.Footnote 174 Around 500 students graduate each year and 80 percent of those who carry out the cooperative portion of their study program at Honduran companies are retained by these companies.Footnote 175

As a result of increasing gang activity and the existence of invisible borders, attendance levels have dropped in recent years for the school in Chamelecón.

Footnote 176 In addition to requesting police assistance, the Municipality of San Pedro Sula is working with military forces, which patrol the invisible borders in order to ensure that the area of the technical school is more secure.

Footnote 177 Nonetheless, the Directorate of Social Services of the Municipality of San Pedro Sula noted the difficulty in recruiting and retaining school instructors for the school in Chamelecón.

Footnote 178 According to the same source, the majority of youth who attend the education centres are youth who have been affected by internal displacement, as a result of the security issues in the areas where they used to reside.Footnote 179

The Local Plan for Citizens' Coexistence and Security (Plan Local de Convivencia y Seguridad Ciudadana, PLCSC) is a government plan that seeks to coordinate municipal efforts to prevent violence.Footnote 180 The PLCSC incorporates municipal agencies, the private sector, civil society, and academia.Footnote 181 Through the PLCSC, the municipality of San Pedro Sula has been accessing high-risk communities to deliver social programs and provide protection.Footnote 182 However, the Municipality of San Pedro Sula indicated that the PLCSC has not been effective in reducing internal displacement.

Footnote 183

Another program is the creation of Outreach Centres (Centros de Alcance), a government initiative, in collaboration with the United States Agency for International Development (USAID), to provide social programs to prevent violence inside conflict-affected communities.

Footnote 184 There are approximately 40 Outreach Centres across the most conflict-affected neighbourhoods of the country,

Footnote 185 including in Tegucigalpa, Comayagüela, San Pedro Sula, Choloma, La Ceiba and Puerto Lempira.Footnote 186 More than 30,000 youth have benefited from the Outreach Centres.Footnote 187

The Honduran government initiated PLAN, a program created by the Office of the President, to provide assistance in Tegucigalpa to at-risk youth and persons who were former gang members.Footnote 188 PLAN consists of community workers who are sent to areas with a high prevalence of violence to provide programs, including psychological assistance, legal advice, the removal of gang-related tattoos, as well as individual and group therapies.Footnote 189 PLAN helps youth who were former gang members to change their appearance, so that they are able to move from their neighbourhoods and find work or study elsewhere.Footnote 190 Approximately 60 youth who were internally displaced, and have been assisted by PLAN, have been able to relocate to other neighbourhoods, changing their lifestyles completely.Footnote 191 PLAN enters communities without being accompanied by the army or the police, so as not to be perceived as a threat to the community.Footnote 192 While PLAN does not have a shelter for its clients, it does have agreements with shelters, including for persons with addictions and for persons who have problems with gangs.Footnote 193 In addition, PLAN offers support to individual shelters, as needed, including operational support.Footnote 194

The mission learned that various NGOs have support and development programs in place, including violence prevention programs, to serve the needs of children and youth, such as the NGOs that are part of the UNHCR-led Protection Working Group (Grupo de Protección) in San Pedro Sula and Tegucigalpa. The mission learned that the Protection Working Group includes nine UN agencies and 17 NGOs who work together in order to: strengthen national protection mechanisms on forced displacement; ensure the safety of humanitarian personnel; share information on protection-related issues and; carry out advocacy on protection-related issues. World Vision, which is part of the Protection Working Group, carries out various programs and projects directly affecting children in communities with high levels of violence.Footnote 195 For example, in the district of San Miguel in Tegucigalpa, World Vision serves 19 communities. One of its development programs is called

Cerro de Plata, which assists 2500 girls and boys.Footnote 196 In addition, World Vision carries out projects focused on the prevention of violence and the promotion of a culture of peace, as well as a technical project for the development of the life skills of children and adolescents.

Footnote 197 World Vision expressed that it is difficult to retain children in their programs, as children are constantly targeted by gangs.

Footnote 198 Children have had to drop out of World Vision's programmes as a result of being forced to flee their community.

Footnote 199 Despite this, the work of World Vision is widely respected within communities, given its religious affiliation and that its work is carried out alongside the church and religious leaders.Footnote 200 Claudia Flores indicated that church groups also carry out development programs for children in neighbourhoods and communities and that such programs are appreciated, even among gang members and organized crime members, due to the level of respect that exists for the church.Footnote 201

2.5 Complaints Mechanism

Rather than filing their complaint with the police, victims of crime carried out by criminal groups prefer filing their complaint with civil society organizations

Footnote 202 or CONADEH.Footnote 203 CONADEH receives 3 to 5 complaints per day from victims of crime, mainly regarding extortion and threats from gangs.Footnote 204 The mission learned that people mistrust state institutions, as there are reports of collusion between government authorities and criminal organizations, including gangs.

Footnote 205 Government authorities are threatened by criminals, who do so in order convince the authorities to act against their victims who file complaints.Footnote 206

Several interlocutors indicated that people regard complaints mechanisms as inefficient.Footnote 207 If a victim of crime does file a report, it is out of "formality" and not because the victim expects authorities to do something about it.Footnote 208 The mission learned that, oftentimes, when victims of crime file a complaint, police officers indicate that the case is not under their jurisdiction or that the IT system is down.

PMH indicated that officers receiving the complaints are not adequately trained to do so.

Footnote 209 Oftentimes, they warn victims about the risk that they are taking by filing a complaint.Footnote 210 The mission learned that criminal groups have banderas outside police stations and Public Ministry offices monitoring who is filing complaints. The mission learned that there have been cases of victims who have been killed shortly after filing a complaint.

3. Displacement

In addition to learning that displacement is prevalent in Honduras, the mission learned that causes of displacement include generalized violence, threats, extortion, forced recruitment of minors by gangs, poverty, especially in rural areas, and land/house-grabbing. People are also displaced by violence caused by criminal organizations, particularly gangs.Footnote 211 State agents are also accused of causing displacement, often acting in collusion with criminal organizations and enterprises.Footnote 212 The mission learned that internal displacement also occurs due to family feuds,Footnote 213 the construction of megaprojects,Footnote 214 and the exploitation of natural resources.Footnote 215 PMH has documented cases of people being threatened so that they leave their area of residence and megaprojects can be built.Footnote 216

Most cases of displacement begin as internal in nature; however, it is common that IDPs eventually seek to leave the country.Footnote 217 Usually, parents migrate first and leave their children behind with other relatives who will, in turn, eventually send the children on the migratory route to be reunited with their parents.

Footnote 218 The majority of IDPs across Honduras, however, consist of entire families.Footnote 219 It is very common that entire families leave their homes in order to protect their children from forced recruitment.Footnote 220 The family unit is an important element in Honduran society.Footnote 221 When family members stay behind, gangs pressure remaining relatives to provide information on the whereabouts of the targeted person.Footnote 222 It is also feared that remaining family members will be targeted by gangs as a form of retaliation.Footnote 223

On 31 March 2014, the Honduran government officially swore in the Interinstitutional Commission for the Protection of Displaced People Due to Violence (Comisión Interinstitucional para la Protección de Personas Desplazadas por la Violencia),Footnote 224 which was created by Executive Decree Number (Decreto Ejecutivo Número) PCM-053-2013,Footnote 225 with the mandate to [translation] "formulate policies and adopt measures to prevent forced displacement, as well as to assist, protect and provide solutions to displaced people and their families."Footnote 226 The Commission is comprised of 10 government institutions and 5 civil society organizations.Footnote 227

One of the Commission's main achievements is its ability to provide information on the number of displaced persons, their areas of resettlement, their needs, and the root causes of their displacement.Footnote 228 In 2015, the Commission published a study with statistical information on the number of displaced persons between 2004 and 2014.Footnote 229 The study, titled Characterizing Internal Displacement in Honduras (Caracterización del Desplazamiento Interno en Honduras), provides an analysis on internal displacement in the country based on a survey of displaced and non-displaced persons in 20 municipalities in 11 departments.Footnote 230 The report indicates that approximately 174,000 people, divided into approximately 41,000 households, have been displaced between 2004 and 2014, and that 7.5 percent of these people were in their second displacement, and 2.1 percent in their third displacement.Footnote 231 According to the Internal Displacement Monitoring Centre (IDMC), as of 31 December 2016, there were 190,000 internally displaced persons (IDPs) in Honduras.Footnote 232

In 2016, CONADEH received 694 complaints of forced displacement, out of which 345 petitioners were at risk of displacement, and 349 were already displaced.Footnote 233 CONADEH indicated that it is very difficult to determine how many people are in a situation of internal displacement due to violence, as many of them do not file complaints.Footnote 234 PLAN indicated that filing a complaint due to displacement can expose complainants to retaliation by aggressors.Footnote 235 PLAN indicated that, for example, when students are threatened or face forced recruitment by gangs, they prefer internal displacement over filing a complaint, because submitting a complaint could lead to their death.Footnote 236

Radio Progreso indicated that, according to Casa Alianza, there are 1 million youth in Honduras and that, while they are able to study or work, they neither study nor work.Footnote 237 While youth flee internally as a first step, they opt for the migratory route, in part due to the lack of access to education and work.Footnote 238

IDPs arriving in San Pedro Sula usually inhabit areas near the river banks (bordos), which are not suitable living environments due to a lack of access to potable water, electricity and basic sanitary conditions, and where flooding is also frequent.Footnote 239 Radio Progreso indicated that people living in bordos are discriminated against in the job market, because employers refuse to hire people living in these areas.Footnote 240 The mission learned that people living in high-risk communities, including in Rivera Hernandez and Chamelecón in San Pedro Sula, face similar employment discrimination. People migrate to the cities in search of stable economic livelihoods; however, since there are not enough opportunities available in the larger cities, nor are there options in agricultural development in rural areas, many of them end up taking the migratory route.Footnote 241

3.1 Assistance for Internally Displaced Persons (IDPs)

The Interinstitutional Commission for the Protection of Displaced People Due to Violence has a budget of 12 million HNL [approximately C$637,440], which, according to a SDHJGD representative, is not enough to assist displaced persons in Honduras.Footnote 242 According to SDHJGD, so far, the Commission has only developed draft action plans, without implementation.Footnote 243 Even though the state has recognized the problem of internal displacement, it has not been able to address this problemFootnote 244 and no clear protection mechanism exists.Footnote 245 Interlocutors also indicate that the state is not prepared to deal with internal displacement and victims are sent from one state institution to another in order to find a solution for their displacement, to no avail.Footnote 246

The mission learned that, in practice, NGOs,Footnote 247 international organizations and churches are the entities that have been addressing internal displacement.Footnote 248 The Honduran government refers cases of internal displacement to organizations such as UNHCR, the International Committee of the Red Cross (ICRC), and NRC.Footnote 249

NRC, which has been operating in Honduras since 2015, carries out two main programs: an educational programme and the ICLA programme.

Footnote 250 The ICLA programme provides guidance, information and legal assistance to families and individuals who have been displaced as a result of violence.Footnote 251 Additional services include the provision of temporary shelter, food, support to relocate in Honduras, and, with help from Doctors Without Borders psychological care.Footnote 252 The educational programme works with children who fall outside of the official school system as a result of displacement, or, as a result of being returned to Honduras after attempting to take the migratory route.Footnote 253 NRC indicated that the children it serves through its educational programme are often fleeing gang recruitment.Footnote 254 NRC is able to identify which children have fallen outside of the school system by means of a census that its volunteers carry out in violent and vulnerable communities in Tegucigalpa and San Pedro Sula and through organizations like Centro Belén.Footnote 255 NRC indicated that there are families who, once displaced, choose not to register their children in the educational system, fearing that the family's relocation will be known.Footnote 256 NRC further indicated that when there are no government or NGO programs or shelters to protect children who face violence or recruitment from gangs, parents choose to keep their children locked up within their house.Footnote 257 Alternatively, children are sent to live with relatives in rural areas.Footnote 258

Casa Alianza has been providing assistance to people in 31 cases of forced displacement due to violence, including 12 cases of internal displacement and 19 cases involving migrants.Footnote 259 In 60 percent of these cases, victims have suffered the loss of a relative due to violence.Footnote 260 Casa Alianza works with: children who receive death threats from organized crime groups or gangs; children that have been or can be recruited by organized crime groups or gangs; children whose relatives are directly connected to organized crime groups or gangs; children experiencing sexual violence; children who were witnesses of a crime; and children affected by internal displacement or migration.Footnote 261 At its office in Tegucigalpa, Casa Alianza offers a residential programme with comprehensive care for children between 12 to 18 years old in the areas of academics, psychology and physical health.Footnote 262 Admission to Casa Alianza's residential programme is voluntary, and the permission of the child's mother, father or guardians is required.Footnote 263 With its residential programme, Casa Alianza is able to host up to 120 children every night.Footnote 264

Casa Alianza also offers another residential programme in Tegucigalpa, called Querubines, for children between the ages of 12 and 17 years old who are victims of human trafficking.Footnote 265 The only requirement for the Querubines programme is the need for protection, because admission to the programme is voluntary.Footnote 266 Casa Alianza indicates on its website that the “majority of the victims arrive at Querubines via a judicial order from a judge or prosecutor.”Footnote 267 Through the Querubines programme, Casa Alianza is able to house 25 girls at once, providing care “for an average of 30 to 50 girls per year, who stay for varying amounts of time.”Footnote 268 Through its presence in San Pedro Sula, Casa Alianza also offers comprehensive care to children who are not able to attend Casa Alianza's residential programme and who remain with their families.Footnote 269 Consequently, Casa Alianza provides them with comprehensive care in the areas of physical health, dentistry, ophthalmology, psychiatry and food.Footnote 270

The mission learned that UNHCR provided four protection alternatives in 2016: 1) internal relocation; 2) humanitarian evacuation; 3) Protection Transfer Arrangements; and 4) guidance on international protection. In addition, the mission learned that these alternatives are implemented with UNHCR resources in coordination with the NGOs PMH, Casa Alianza, NRC, Caritas de Honduras, and the Mennonite Social Action Committee (Comisión de Acción Social Menonita). UNHCR indicated that 2,230 IDPs were assisted in 2016, while 1,930 IDPs were assisted between January and June 2017.Footnote 271

While the state does not have protection homes available for children, the Directorate of Children, Women and Family of the Municipality of San Pedro Sula indicated that it does support protection homes for children that are provided by NGOs.Footnote 272 SDHJGD indicated that while there are shelters for children, there are no shelters for families as a whole.Footnote 273 If a child is threatened by a gang, admission to a shelter might be denied, because the child may pose a threat to the rest of the children in the shelter.Footnote 274

The mission learned that there have been cases of NGO workers being threatened or attacked by criminal organizations.Footnote 275 World Vision indicated that it is common that organizations, including UNHCR, Casa Alianza, World Vision, and the Directorate for Children, Adolescents and Family (Dirección de Niñez, Adolescencia y Familia, DINAF), are unable to assist victims of gang violence, as it could endanger someone in their organization.Footnote 276

4. Returnees

A report produced by the National Centre for Information on the Social Sector

(Centro Nacional de Información del Sector Social, CENISS), the government agency responsible for providing information to the Presidential Office (Despacho Presidencial), including on the creation of programs, projects and social policies,Footnote 277 indicates that between 1 January and 31 July 2016, 27,137 people were repatriated/returned to the country,Footnote 278 of which 5,284 were minors.Footnote 279 The same report indicates that between January 2014 and July 2016, 95,250 people were returned to the country, of which 11,884, or 12.48 percent, had been returned more than once before.Footnote 280 NRC similarly indicated that there are many cases of returnees retaking the migratory route.Footnote 281

The mission learned that there are a significant number of cases where returnees were killed shortly after they returned to Honduras.Footnote 282 According to PMH, there are cases of people who left Honduras, due to gang or organized crime-related violence, who were killed shortly after returning to San Pedro Sula.Footnote 283 PMH indicated that some press reports attribute these crimes to theft or robbery, even though, in many cases, deportees arrive without any belongings.Footnote 284

4.1 Assistance for Returnees

The mission learned that there are three Centres of Assistance for Returned Migrants (Centros de Atención a los Migrantes Retornados, CAMRs), namely in Omoa, La Lima, and San Pedro Sula. The mission learned that the CAMR in Omoa is administered by the Red Cross and receives adults deported from Mexico. It assists returnees upon their arrival in Omoa with their registration, the provision of food, health services, clothing, transportation to the bus terminal, and accommodation for a maximum of 100 persons.Footnote 285 The mission learned that the CAMR in La Lima is administered by the Congregación de las Hermanas Scalabrinianas [Congregation of Scalabriniana Sisters] and that it receives adults deported from the US. The mission further learned that the CAMR in San Pedro Sula, which is known as CAMR Belén, is administered by DINAF and receives children and families who are deported from Mexico and the US.

In March 2017, Municipal Units for Assistance to Returned Migrants (Unidades Municipales de Atención a Migrantes Retornados, UMAR), were opened in San Pedro SulaFootnote 286 and the Central District, to help [translation] "reduce the number of cases of returnees retaking the migratory route."Footnote 287 In August 2017, an UMAR was opened in Choloma, in the neighbourhood El Centro.Footnote 288 UMARs assist families who are returned from the US and Mexico with community reintegrationFootnote 289 and provide returnees with psychological, educational and employment support.Footnote 290

DINAF is a state institution that provides policies and regulations for the comprehensive protection of the rights and well-being of children, youth and families in Honduras.Footnote 291 According to the Directorate of Children, Women and Family of the Municipality of San Pedro Sula, DINAF attends to cases involving children in gangs and assists them with their relocation.Footnote 292 The Directorate of Children, Women and Family of the Municipality of San Pedro Sula indicated that it supports returned children through DINAF in various aspects such as social assistance, including helping with their registration and paperwork, and legal assistance.Footnote 293 The Municipality of San Pedro Sula also follows up on the reinsertion of children in the school system, as well as with the relatives of returned children so that they can attend the municipal training centres where free vocational training is provided for women, including mothers.Footnote 294

Interlocutors indicated, however, that social programs available for returnees are limitedFootnote 295 and only a fraction of returnees benefit from them.Footnote 296 NRC indicated that there are no school integration programs for children returnees provided by the Ministry of Education.Footnote 297 NRC added that it has heard of cases where children returnees experienced bullying at school, because they are returnees.Footnote 298 NRC itself offers assistance programs for returnees, including school enrollment for children, food, and a temporary shelter for those wishing to relocate internally.Footnote 299

Chapter II - Violence against Women and Girls

1. Situation

The mission learned that women and girls face various forms of violence and that violence against women and girls continues to be widespread across Honduras. Grupo Sociedad Civil (GSC) indicated that there is a "war against women" in Honduras and that women face various levels of violence, including domestic violence (violencia doméstica) and violence carried out by organized criminal groups.Footnote 300 The same source indicated that these acts of violence can ultimately lead to femicide,Footnote 301 which the World Health Organization (WHO) describes as the "intentional murder of women because they are women."Footnote 302

The Observatorio de Violencias Contra Las Mujeres (Observatory of Violence against Women) of the NGO Centro de Derechos de Mujeres (CDM) (Centre for Women's Rights), which has offices in Tegucigalpa and San Pedro Sula, provides the following statistics on 752 cases of violence against women that occurred between January 2016 and December 2016, according to data collected through the monitoring of written media reports at the national level:Footnote 303

| Types of Violence | Victims | Percentage |

|---|

| Sexual harassment | 2 | 0.3 |

| Acts of lust | 45 | 6 |

| Commercial sexual exploitation | 113 | 15 |

| Multiple homicides and massacre | 44 | 5.9 |

| Attempted homicide | 14 | 1.9 |

| Attempted sexual violence or statutory rape | 4 | 0.5 |

| Injury | 51 | 6.8 |

| Violent death | 276 | 36.7 |

| Violent death and sexual violence | 11 | 1.5 |

| Rape | 4 | 0.5 |

| Sexual violence or rape | 142 | 18.9 |

| Domestic violence | 21 | 2.8 |

| Intrafamily violence (violencia intrafamiliar) | 25 | 3.3 |

In 2016, CONADEH received 1,786 complaints from women related to the right to life and personal integrity, including on the basis of death threats, maltreatment, intimidation, and duress.Footnote 304 346 of these complaints were related to domestic violence, while 48 complaints were related to intrafamily violence.Footnote 305

The Observatorio de Violencias Contra Las Mujeres of CDM provides the following statistics on 306 cases of violence against women that occurred between January 2017 and June 2017, according to data collected through the monitoring of written media reports at a national level:Footnote 306

| Types of Violence | Victims | Percentage |

|---|

| Sexual harassment | 3 | 1.0 |

| Acts of lust | 18 | 5.9 |

| Commercial sexual exploitation | 8 | 2.6 |

| Multiple homicides and massacre | 15 | 4.9 |

| Attempted homicide | 2 | 0.7 |

| Attempted sexual violence or statutory rape | 16 | 5.2 |

| Injury | 36 | 11.8 |

| Violent death | 99 | 32.4 |

| Violent death and sexual violence | 6 | 2.0 |

| Rape | 2 | 0.7 |

| Sexual violence or rape | 96 | 31.4 |

| Domestic violence | 3 | 1.0 |

| Intrafamily violence (violencia intrafamiliar) | 2 | 0.7 |

2. Forms of Violence against Women and Girls

2.1 Domestic Violence versus Intrafamily Violence

Dr. Ayestas indicated that in Honduras, domestic violence and intrafamily violence are problems.Footnote 307 In Honduras, however, there is a difference between the concepts of domestic violence and intrafamily violence.Footnote 308 While domestic violence concerns violence between partners, intrafamily violence concerns violence involving members of the traditional nuclear family, including fathers who assault their daughters.Footnote 309 Dr. Ayestas indicated that a culture of violence exists within households and that, according to information from the National Observatory of Violence of UNAH, the primary perpetrators of violence against women and girls are parents, uncles, and cousins.Footnote 310 Domestic violence is not criminalized and is addressed in domestic violence courts (juzgados de violencia doméstica), whereas intrafamily violence is addressed in criminal courts,Footnote 311 as intrafamily violence is considered a crime.Footnote 312 According to the Directorate of Children, Women and Family of the Municipality of San Pedro Sula, if a domestic violence case is recurrent, it could be considered to be intrafamily violence, but this does not mean that a woman must exhaust the domestic violence complaints process before filing a criminal complaint.Footnote 313 Nonetheless, the majority of complaints are treated as cases of domestic violence.Footnote 314

2.1.1 Domestic Violence

Sources indicated that domestic violence is an issue in HondurasFootnote 315 and has been a reason why women leave the country.Footnote 316 Article 5 of the 2006

Law against Domestic Violence and its Reforms (Ley Contra la Violencia Doméstica con sus Reformas) provides the following:

Article 5.

The following meanings shall apply for the purposes of this Law:

-

Domestic Violence: All patterns of conduct associated with a situation of unequal exercise of power that is manifested in the use of physical, psychological, patrimonial and/or economic and sexual violence; and

-

Unequal Exercise of Power: All behaviour aimed at affecting, compromising or limiting free development of the personality of the woman for reasons of gender.

The following are considered forms of domestic violence:

-

Physical Violence: Any action or omission that damages or impairs the bodily integrity of a woman that is not criminalized in the Criminal Code;

-

Psychological Violence: Any action or omission whose purpose is to degrade or control the actions, behaviours, beliefs and decisions of a woman through intimidation, manipulation, direct or indirect threat, humiliation, isolation, confinement or any other conduct or omission involving injury to her integral development or self-determination, or that causes emotional harm to a woman, lowers her self-esteem, impairs or disturbs her healthful development, through the exercise of acts of discrediting a woman, contempt for personal value or dignity, humiliating or debasing treatment, monitoring, isolation, insults, blackmail, degradation, ridicule, manipulation, exploitation or threats to take children away, among others;

-

Sexual Violence: Any conduct involving threat or intimidation that affects the integrity or sexual self-determination of women, such as unwanted sexual relations, denial of contraception and protection, among others, provided that such actions are not classified as a crime in the Criminal Code; and,

-

Patrimonial and/or Economic Violence: Any act or omission involving the loss, transformation, negation, removal, destruction or retention of objects, personal documents, movable property and/or real estate, securities, rights or economic resources used to meet the needs of a woman or family group, including impairment, reduction or negation affecting a woman's income or non-compliance with support obligations.Footnote 317

The 2006

Law against Domestic Violence and its Reforms, which is based on the OAS

Inter-American Convention on the Prevention, Punishment and Eradication of Violence against WomenFootnote 318 (also known as the

Bélem do Para Convention), is attached to this Report (Attachment 2)

2.1.2 Intrafamily Violence

Intrafamily violence is addressed in Chapter V of Title IV of Book II of the

Penal Code (Código Penal), which is attached to this Report (Attachment 3). GSC indicated that the penalty for intrafamily violence is "very low" and that civil society is fighting for a new penal code to increase the penalty for intrafamily violence.Footnote 319 GSC further stated that it is also advocating for a comprehensive law on violence against women.Footnote 320

2.2 Femicide

The mission learned that there is a high prevalence of femicide in Honduras, with a rate of one woman killed every 16 hours,Footnote 321 just for being a woman.Footnote 322 In July 2017, women's rights defenders and organizations declared a “red alert” (alerta roja) for the high rate of femicides in Honduras.Footnote 323

According to the UN Economic Commission for Latin America and the Caribbean (ECLAC), 531 women were killed in Honduras in 2014, which represents a femicide rate of 13.3 per 100,000 women.Footnote 324 The Observatory for Violent Deaths of Women and Femicides (Observatorio de Muertes Violentas de Mujeres y Femicidios) of UNAH reported that 478 women were subjected to violent death or femicide in 2015,Footnote 325 which represents an average of 40 women per month.Footnote 326 Sixty-nine percent of these deaths occurred in urban areas, while 31 percent occurred in rural areas.Footnote 327 The departments with the highest number of women subject to violent death or femicide are Cortés (31.2 percent) and Francisco Morazán (26.6 percent), followed by Yoro (6.7 percent), Atlántida (4.8 percent), and Olancho (4.6 percent).Footnote 328 The data collected by the Observatorio de Violencias Contra Las Mujeres of CDM indicates that the violent deaths of women that happened between January 2016 and June 2017 occurred in the following departments:

| Department | Victims in 2016Footnote 329 | Victims in 2017Footnote 330 | Victims January 2016 - June 2017 |

|---|

| Atlántida | 15 | 10 | 25 |

| Choluteca | 5 | 2 | 7 |

| Colón | 6 | 3 | 9 |

| Comayagua | 6 | 4 | 10 |

| Copán | 10 | 1 | 11 |

| Cortés | 112 | 47 | 159 |

| El Paraíso | 7 | 3 | 10 |

| Francisco Morazán | 116 | 45 | 161 |

| Gracias a Dios | 2 | | 2 |

| Intibucá | 3 | 2 | 5 |

| Isla de la Bahía | 1 | 1 | 2 |

| La Paz | 3 | 1 | 4 |

| Lempira | 3 | 1 | 4 |

| Octepeque | 1 | 4 | 5 |

| Olancho | 11 | 1 | 12 |

| Santa Bárbara | 8 | 6 | 14 |

| Valle | 2 | 2 | 4 |

| Yoro | 20 | 8 | 28 |

The mission learned that the existing homicide rates issued by state officials in Honduras are not conclusive and the actual rate may be higher, as not all homicides are recorded. PMH explained that homicides are not always recorded because state officials, like the police and the forensic unit of the Public Ministry, do not always have access to gang-controlled neighbourhoods where homicides take place, and because family members of the victims are threatened by gangs so they do not report the homicide or bury bodies in an official manner.Footnote 331 PMH provided the example of a 16-year-old girl who refused to be recruited by a gang to perform sexual acts, and was subsequently raped by eight gang members and then killed.Footnote 332 The gang members demanded that an 11-year-old child bury the body of the 16-year-old girl in secret, and threatened to kill the remaining children of the family if the family members spoke out.Footnote 333

The

Penal Code, which was reformed in 2013 with

Decree No. 23-2013

(Decreto No. 23-2013), adding Article 118-A, provides the following:

Article 118-A. The crime of femicide is committed by a man or men who kill(s) a woman for reasons of gender, with hatred and contempt over the fact that she is a woman, and is punishable with thirty (30) to forty (40) years in prison when one or more of the following circumstances is in effect:

- When the perpetrator of the offence has or has had a couple’s relationship with the victim—whether involving marriage, a domestic partnership, a common-law union or any other similar relationship, whether or not there is or has been cohabitation, and including when there is or has been a sentimental relationship;

- When the offence is preceded by acts of intra-family domestic violence, whether or not a complaint has been filed;

- When the offence is preceded by a situation of sexual violence, harassment, intimidation or persecution of any nature; and,

- When the offence is committed with cruelty or when deprecating or degrading injuries or mutilations have been inflicted prior to or following the taking of life.Footnote 334

Radio Progreso explained that it is common for the media to justify acts of femicide by reporting that the murdered women had been unfaithful to their partner.Footnote 335 Radio Progreso indicated that perpetrators of femicide often remain unidentified and that many of them do not appear in police reports or in forensic reports, especially in rural areas.Footnote 336

2.3 Sexual Violence

Sources indicated that adolescent women, in particular, are vulnerable to sexual attacks and sexual violence.Footnote 337 According to Asociación Calidad de Vida (ACV), there has been an increase in the sexual abuse of girls in rural areas.Footnote 338 PLAN indicated that girls between the ages of 12 and 15 living in rural areas are vulnerable to being targeted by drug lords who wait for them outside of schools.Footnote 339 ACV provided the example of a group of girls who were raped while traveling to school in a rural area.Footnote 340 One girl had consequently become pregnant, but was accused of abortion when she lost the baby.Footnote 341 Given that abortion is criminalized in Honduras,Footnote 342 she was sent to jail.Footnote 343 GSC indicated that women are also vulnerable to human trafficking and sexual exploitation.Footnote 344 The same source provided the example of a case where church pastors were involved in the trafficking of girls.Footnote 345

Out of the 1,786 complaints in 2016 by women related to the right of life and personal integrity, CONADEH registered 17 complaints of sexual violence from women.Footnote 346 The mission learned that survivors of sexual violence often do not file a report as a result of fear of the aggressor, shame, or due to a lack of confidence in the justice system, for example.Footnote 347

Forms of sexual violence, including rape and sexual harassment, are addressed in Chapter I of Title II of Book II of the

Penal Code, which is attached to this Report (Attachment 4).

2.4 Gang Violence against Women and Girls

The mission learned that gangs subject women to various forms of violence and that they seek to exert control over women, including their bodies. GSC provided the example that gangs establish rules on how women should dress and what their hair colour should be, including prohibiting them from dyeing their hair, unless they belong to a certain gang or criminal organization, as well as prohibiting them from wearing purses that show crosses, as this is regarded to have a symbolic meaning.Footnote 348 GSC also explained that women's bodies are used for revenge; gang members may seek to kill the wife or children of an adversary as a form of retribution.Footnote 349

The mission learned that girls have been forced to carry out gang-related activities.Footnote 350 GSC provided the example of a neighbourhood where youth, including girls, were killed for not wanting to sell drugs.Footnote 351 Girls have also been subject to extortion.Footnote 352 GSC provided an example of an incident that occurred in 2016, where girls between the ages of 13 and 15 years old were found dead (dismembered in bags) because they had refused to pay a gang's war tax.Footnote 353